What Is Social Practice Anyways? A Look at Chicago’s “A Lived Practice”

http://artfcity.com/2014/11/17/what-is-social-practice-anyways-a-look-at-chicagos-a-lived-practice/

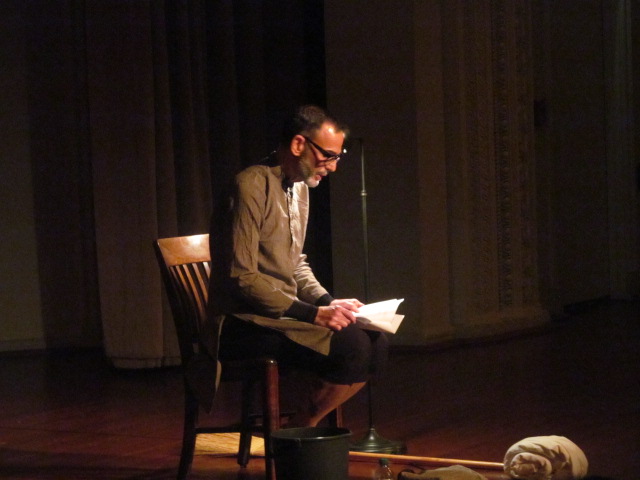

Ernesto Pujol, “The Art of Consciousness,” at Chicago’s Lived Practice symposium.

Does Chicago describe social practice differently than New York? After attending “A Lived Practice,” a social-practice symposium at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I would say yes. More than any other discussion of social practice I’ve heard, there is a vested interest in referring to it as a “lived practice,” an art that seeks to create outcomes that will change the future.

Not all definitions of social practice are so future-oriented, or need to be defined as life-long projects. Tom Finkelpearl, former executive director of the Queens Museum and current New York City cultural commissioner defines social practice as “art that’s socially engaged, where the social interaction is at some level the art.” Creative Time’s Living as Form, describes social practice as works “that emphasize participation, challenge power, and span disciplines ranging from urban planning and community work to theater and the visual arts.”

From my point of view, these definitions are confusing. What does the social even mean? Is it micro or macro? Does it need to be activist? Like Post-Internet, and relational aesthetics beforehand, social practice seems to be in the running for the most widely applied term with a definition few can agree upon. All said, this is why we need to do more talking—and why more symposiums need to exist—in order to figure out why on earth this type of work has experienced a rise in visibility over recent years.

“A Lived Practice” is part of a larger initiative at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, one part of A Proximity of Consciousness: Art and Social Action, curated by Mary Jane Jacob and Kate Zeller at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In conjunction with the exhibition’s run (it closes on December 20, 2014), the show’s curators organized a series of lectures, publications (an impressive set of four volumes on social practice history), and a symposium.

After spending a weekend in the city for “A Lived Practice,” my takeaways about social-practice in Chicago seems to rely on a fairly strict description: long-term, local initiatives by artists are preferred to fly-by-night projects; one’s life must be ethically rooted in the work; and the city’s activist history has helped spur social-practice today. Mentions of early 20th century activist Jane Addams and philosopher John Dewey abound in the press materials and publications, naming those two as historical precedents for artists who merge art and life. It is, of course “a lived practice,” not a hobby. (The fact that Dewey and Addams were chosen were intentional; the two have close ties to Chicago, and, to my knowledge, are not mentioned all-too often in literature regarding social practice outside of New York.)

The symposium itself was composed of hour-long lectures by Crispin Sartwell, philosopher; Ken Dunn, activist; Wolfgang Zumdick, art historian; and Ernesto Pujol, performance artist. Overall, each speaker brought a different tone—from Sartwell’s lighthearted chit-chattiness to Zumdick’s serious academicism—which did make it hard to shift between talks. What did stick out as a common thread among speakers was an interest in John Dewey, in particular how art should not be isolated from culture; the two can form a “coherent and integrated imaginative union.” (I’m still confused about why none of the speakers were women; an oddity considering the sheer number of women involved in the field.)

Sartwell began his talk by John Dewey as an influence before going on to discuss how pop culture, craft, and fine art should be on the same level—“an aesthetic approach that enriches all experience.” He brought up Taylor Swift as an example of an under-recognized figure in the arts, whose fangirl audience appreciates her work on a level of aesthetic experience. What pop culture writer Crispin Sartwell could add to a discussion of artworks outside the market (he tended towards examples like Jeff Koons and Taylor Swift), left many people guessing. Basically, I took Sartwell’s talk to be a contemporary update on high- and low-art—which, hadn’t we gotten rid of when we tossed out the ideas of Clement Greenberg?

Vocal members of the audience didn’t seem to think so; they railed on Sartwell for his Taylor Swift-positivity with phrases like “You can be broke and hear Taylor Swift anywhere in the world” or “If you delete capitalism from music of this century, I don’t know what [art] you’d have.” Operating on two seemingly different planets, his statement fell on deaf ears. He was speaking to a room full of artists, some of whom were not too interested in John Dewey’s embrace of all aesthetic experience.

The next speaker proved an antithesis to Sartwell: Ken Dunn. Another student of philosophy, Dunn instead found solace in helping others, specifically the poor, African-American residents surrounding the University of Chicago. In comparison to Sartwell, Dunn gave up on academic life in favor of founding a non-profit recycling center and farm on the South Side of Chicago. He told us about driving local residents in his truck so they could find old bottles to recycle. His farm was able to create jobs. And, he told us, these initiatives, by ridding the city of vacant lots, drug dealers left the area. City Farm is a success story, but Dunn isn’t the best speaker in the world. The talk was filled with generalizations about helping future generations, and then digressions about how both the Internet and terrorism is bad.

By noontime, it became apparent that we’d have to wait until after the lunchtime break to have any discussion of Art. And wait we did, as each speaker had a difficult time staying within their allotted timeframe. During the gap between sessions, we were encouraged to visit the museum’s modern gallery to view Joseph Beuys’s “Untitled (Sun State),” a chalkboard from a 1974 performance in Chicago; after lunch, Wolfgang Zumdick would speak on the topic of Beuys and his chalkboards.

Beuys is seen an incongruous figure in terms of social practice; after all, he coined the term “social sculpture”, which refers to humanity’s ongoing desire to shape the world according to their imagination. While that belief runs deep among many activist artists, his stance that objects could and should be made for the market didn’t sit well with many of these same artists. Naturally, Zumdick cited several historical references that made clear why Beuys would be an uneasy fit within many social-practice circles today. For example, Beuys was a political provocateur.

In 1964, in a Fluxus event (performers included Beuys, Wolf Vostell, and Robert Filliou) at the University of Technology in Aachen, Beuys allegedly spilled hydrochloric acid on stage, provoking a near-riot. He was punched multiple times; the photo below was taken at the event.

Historically, social practice has not always been full of nice, do-good activism. Beuys did not help his neighbors till their gardens; he wanted to motivate them to act on their own. If they were angry, so be it.

The closing speaker brought the day back to the present, with Ernesto Pujol, an artist whose performances often involve groups of participants completing mundane actions. For several years, he lived as a Trappist monk. In “Time After Us,” a 24-hour-long performance held after Hurricane Sandy, performers would walk a circle backwards, unable to see where they were going, and thus, become vulnerable together. Like “Time After Us,” many of his works, though project-based integrated seamlessly with his life, thus making him a perfect choice “A Lived Practice.”

For his lecture, Pujol sat on a stool. Sometimes he swept, or used various props, but mostly, he remained silent. Though silence can be “generative,” Pujol mentioned between a long stretch of speechlessness, it is also the sound of nothingness, and death. Pujol even told the audience “I’m already dead. I’m already long gone.”

More than many activist artists, his embrace was metaphysical, though still rooted in a desire for change. And like Beuys, Pujol was more about piquing the imagination of others into thought, or action. His goals include an art world where we can obtain cultural consciousness through new visions of the future.

This is difficult to achieve in art, nevertheless define. Perhaps a more clear-cut explanation of what living practice means would have been useful. Otherwise, calling it “lived practice” or “social practice,” whatever that means, still creates too much of a division between the hundreds, perhaps thousands, who’ve emerged to identify with socially engaged art—and the other types of artists who would choose to distance themselves from calling their practice anything other than art.

Comments